Page Contents

Catholics believe that works of charity are an essential part of faith. Catholic hospitals, orphanages, care homes and the St Vincent de Paul Society have been a large part of the Australian charity sector.

Nuns’ charitable work

In the nineteenth century, most orders of nuns originally aimed at charity more than educational work, and in the absence of a welfare state their role was central. By 1900 in NSW, “Sisterhoods operated: five hospitals, including a women’s psychiatric hospital and a hospice; seven orphanages; a foundling hospital; a residential school for deaf children; three industrial schools; a servants’ home and training school; two refuges for former prostitutes; a home for the aged poor and a women’s night refuge. The Sisters also undertook non-institutionally based work with immigrant servant girls; the sick poor in their homes; patients in Sydney Hospital; prisoners in Darlinghurst Gaol; the inmates of government aged asylums and girls in the Government Reformatory and Industrial School.” (Lesley Hughes, Catholic Sisters and Australian social welfare history, ACR 87 (2010) … thesis)

As an example of specialised ministries, Sr Mary Gabriel Hogan, herself deaf, established the Rosary Convent for the Deaf and Dumb in Newcastle in 1875 and it operated for over a century. The Catholic Deaf Association has been active since 1914.

Orphanages

Large number of orphans and, before the era of the Pill, abandoned children, were cared for in institutions, state and religious. Other children from large and poor families in distress were cared for temporarily. Some 130 Catholic institutions provided such care (listed in the Directory of Catholic Institutions Caring for Children Separated from Families). Records for some but not all Catholic orphanages in Victoria total 63,000 children.

The first was the Roman Catholic Orphan School established at Parramatta in the 1840s. An orphanage in Adelaide was among the first works of Mary MacKillop’s Sisters of St Joseph. In the late nineteenth century, Catholic orphanage care expanded greatly while state policy preferred boarding out.

Experiences of those in institutions varied. Some retained happy memories, but many experienced deprivation, through the impersonal nature of underfunded mass care, trauma before admission, and in some cases mistreatment in the homes. The outcomes were diverse. The Church issued an official apology in 2009.

Sadly, the powerlessness of orphans meant they could be easily targeted by abusers. Certain residential care institutions for orphans and disabled and deprived children recorded very high rates of sexual abuse, such as the Western Australian farm schools Bindoon and Tardun, those run by the St John of God Brothers, Neerkol and Boys Town, Beaudesert.

Abbotsford Convent

The massive Abbotsford Convent in Melbourne, founded by the Sisters of the Good Shepherd in 1863, was said to be the largest charitable institution in the Southern Hemisphere around 1900. It operated for 100 years, housing female orphans, Wards of the State, girls considered to be in moral danger and some aged women. Its story is told in Stuart Kells’ The Convent and Catherine Kovesi’s Pitch Your Tents on Distant Shores.

Cecilia Ryan, a former Abbotsford resident, returned and stayed there at the time her son Ronald became the last man to be hanged in Australia.

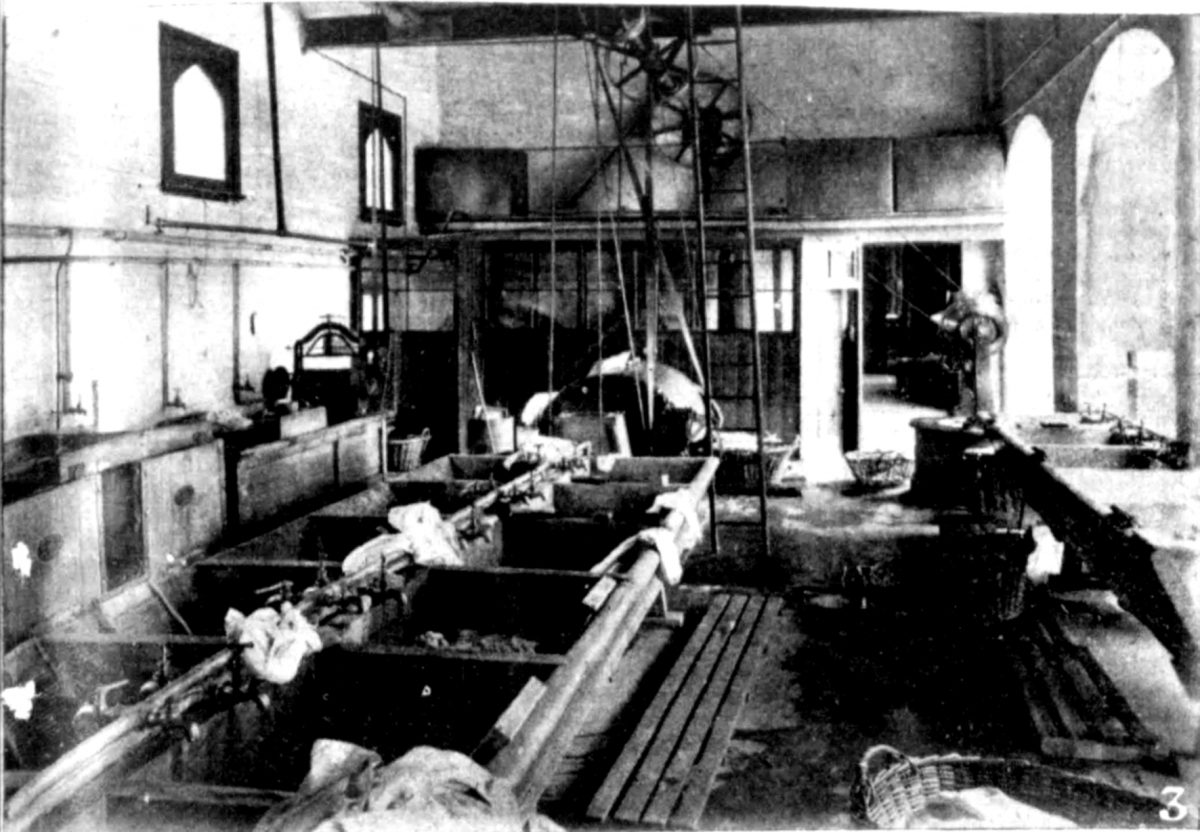

Women’s refuges and Magdalen laundries

The Sisters of Charity founded the House of the Good Shepherd in Sydney in 1848 as a refuge for destitute women. It was later taken over by the new Australian order, the Sisters of the Good Samaritan, as their first work.

The role of refuges conflicted with the use of the homes for court referrals, which gradually transformed Magdalen laundries into, in effect, prisons. Many inmates remember them as oppressive. (a memoir)

Hospitals

The best-known Catholic hospitals are the Sisters of Charity’s St Vincent’s in Sydney and Melbourne.

St Vincent’s Sydney was founded in 1857 by Sr M. John Baptist de Lacy and quickly established a leading reputation. The first successful Australian heart transplant was performed there in 1984. Sr Bernice Elphick was known for her administrative skills and raising large sums of money, especially from heart patient Kerry Packer. Max Coleman’s The Doers: A Surgical History of St Vincent’s Hospital Sydney, 1857-2007 describes the history of treatment at the hospital.

St Vincent’s Melbourne was founded by Sr M. Berchmans Daly in 1893.

The Sacred Heart Hospice for the Dying opened adjacent to St Vincent’s, Sydney, in 1890. A similar hospice in Brisbane opened in 1957. The Sisters of Charity also ran a TB hospital for a period at Parramatta, then Auburn (now a general hospital).

The Sisters of Mercy opened a number of hospitals called Mater Misericordiae: in North Sydney, Brisbane, Townsville, Rockhampton, Mackay, Gladstone and Bundaberg. The Little Company of Mary’s Calvary Hospitals and those of the St John of God sisters, beginning in Western Australia, added to the number.

Gertrude Abbott‘s informal religious community of women ran St Margaret’s maternity hospital in inner Sydney from 1894, initially for unmarried pregnant women. St Joseph’s Foundling Hospital began in Melbourne in 1901 for the same purpose, to take in “erring but often innocent young women” and look after them and their babies. Babies were usually taken from single mothers and adopted out, often forcibly, for which there has been a formal apology.

The influenza epidemic of 1919 saw heroic work by nurses, such as Annie Egan, who died of influenza while nursing patients at the Quarantine Station, Sydney. In Melbourne a sectarian controversy arose when Archbishop Mannix’s offer to provide nursing nuns was rudely received.

The Catholic health care sector now provides about 10% of healthcare services in Australia, with 75 hospitals and 550 residential and community aged care services.

Conscientious objection

A developing issue for Catholic health care has been the conscientious objection of Catholic practitioners and institutions to providing some services that general public hospitals do, such as abortion and euthanasia. So far, the right to conscientious objection stands.

Eileen O’Connor and care in the home

Eileen O’Connor, who died aged 28 in 1921 after suffering severe spinal problems almost all her life, co-founded Our Lady’s Nurses for the Poor (Brown Nurses) to care for the Sydney sick poor in their own homes. The cause for her canonisation is under way.

Maude O’Connell founded the Grey Sisters in Melbourne in 1930 to help poor mothers with housework and respite.

St Vincent de Paul Society

The main Catholic charity for work in the community is the lay-led St Vincent de Paul Society, which has branches (“conferences”) in most parishes. It was brought to Australia by Fr Gerald Ward, who established a conference in Melbourne in 1854. That initiative dissipated but the Society was refounded successfully in Sydney in 1881 by Charles Gordon O’Neill.

From 1902, the Society established conferences to assist seamen, later called the Apostleship of the Sea. A well-known work of the Society is the Matt Talbot Home for homeless men, established in 1938 and now located in Woolloomolloo.

Charity organisation and fundraising

Some women organised charity work on a large scale, such as hospital charity leader Mary Barlow and Lena Santospirito who was very active in welfare work for the Italian community in Melbourne in the 1940s and 1950s.

Edmund Campion‘s Australian Catholics records that the report of the 1967 Moonee Ponds parish fête says ‘The apron bar had sold 250 aprons by early afternoon’, a small indication of the size of parish-based charity fundraising. Raffles and chocolate wheels were big money-spinners though regarded by Protestants as morally dubious.

Father Mac’s Heavenly Puddings on the NSW North Coast sold a million.

Recent times

In recent decades, Catholic charity work has consolidated on the bases of diocesan multi-purpose agencies, such as CatholicCare Sydney and Melbourne. The change in style is recounted in Damian Gleeson’s thesis, The Professionalisation of Australian Catholic Welfare, 1920-1985. There has also been room for special-purpose charities aimed at the most disadvantaged, such as Fr Chris Riley’s Youth off the Streets and the Cana Communities.

Indigenous

Catholic missions were established in remote regions in order to create self-contained communities free of the oppressions and temptations of white society. Fr (later Bishop) Gsell founded a mission on Bathurst Island in 1911 and became known as the “Bishop with 150 wives” for his “purchase” of young promised brides.

Much of the missions’ charitable work involved care of children. Margaret Zucker’s Open hearts: The Catholic Church and the stolen generation in the Kimberley, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 29 (2008), 23-37 argues that the Church was wrongly complicit in government child removal policies. The topic is treated also in Christine Choo’s The role of the Catholic missionaries at Beagle Bay in the removal of Aboriginal children from their families in the Kimberley region from the 1890s, Aboriginal History 21 (1997), 14-29. Gsell argued that removals were necessary as “these creatures [of mixed race] roam miserably around the camps and their behaviour is often worse than that of native children. It is an act of mercy to remove them as soon as possible from surroundings so insecure.”

Garden Point (1940-1962) on Melville Island was established for mixed-race children.

Layman Francis McGarry’s co-founding of a mission in Alice Springs in 1935 is described in Charmaine Robson’s Francis McGarry and the ‘Little Flower’ black mission, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 39 (2018), 107-118.

Mum Shirl‘s work for NSW prisoners and Redfern residents in the 1960s to 1990s is legendary.

Leprosaria

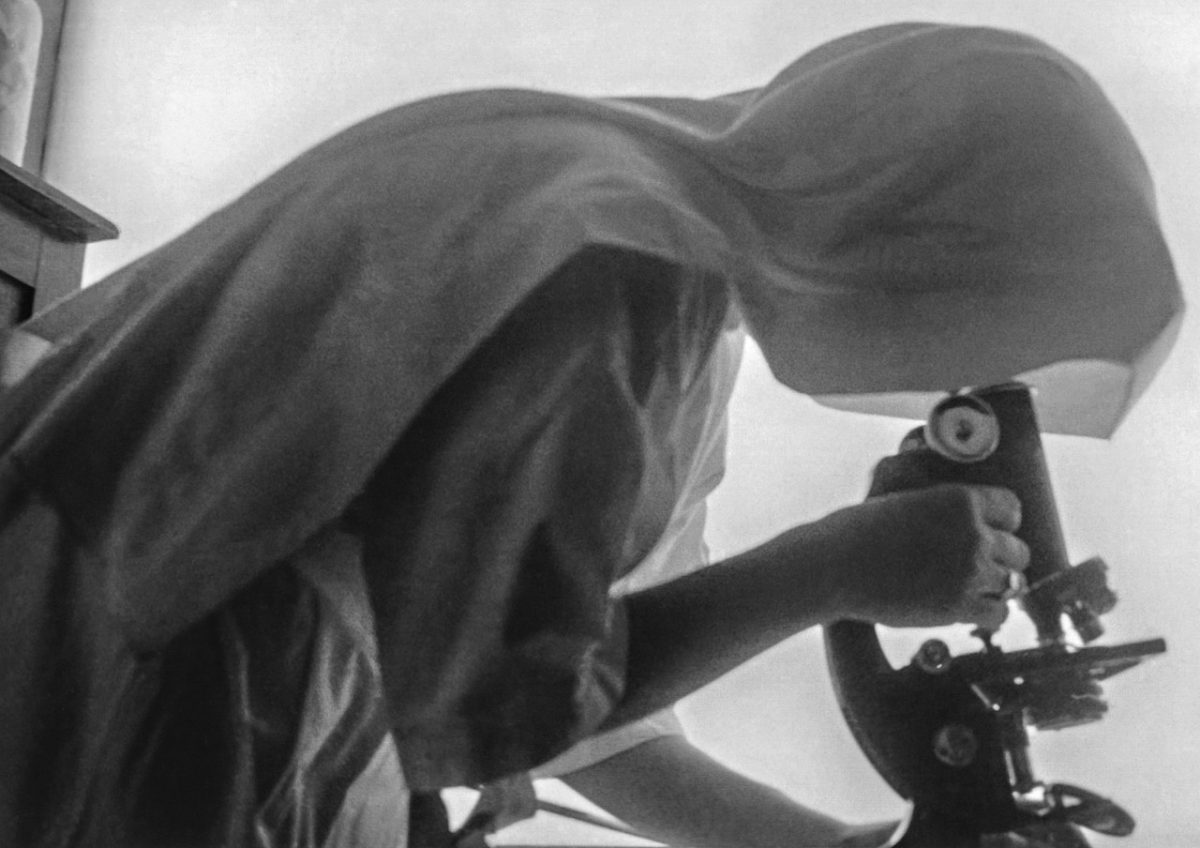

The nursing work of the Sisters of St John of God with indigenous patients in the Derby Leprosarium, led by Mother Mary Gertrude, is recounted in Charmaine Robson’s thesis,

Care and control: the Catholic religious and Australia’s twentieth-century ‘indigenous’ leprosaria 1937-1986. (Footage of the leprosarium lab and orchestra can be seen in the last 5 mins of Stuart Gore’s North-West Diary, 1948)

Aged care

The Sisters of St Joseph established “Houses of Providence” in Adelaide in 1868 and in The Rocks, Sydney, in 1880, whose functions included accommodation for aged destitute women. The Little Sisters of the Poor’s home has operated in Randwick since 1887 and in Melbourne since 1884.

Southern Cross Care was established by the Knights of the Southern Cross in 1968. Catholic Healthcare expanded into aged care from 1998.

Immigrants and refugees

Catholic laywoman Caroline Chisholm responded to the plight of young immigrant women in 1840s Sydney. Her employment agency found safe jobs for many in city and rural areas and her immigration scheme brought many more. The most recent of several books on her and her work is Sarah Goldman’s Caroline Chisholm (JACHS review).

Arthur Calwell, Minister for Immigration, instituted a massive immigration program of Eastern Europeans (many Catholic) from 1947 which transformed Australia from “a dull inbred country of predominantly British stock” to its modern multicultural complexion. It was partly motivated by a wish to assist the destitute refugees from Communism. He was awarded a papal knighthood in recogition.

From 1949, the Federal Catholic Immigration Office, led by Mgr George Crennan, arranged interest-free loans to help some 60,000 poor migrants come to Australia. Controversy arose over child migration. Such work has been continued by the Jesuit refugee service.

More recently the St Bakhita Centre has assisted Sudanese refugees. St Bakhita is also patroness of efforts to combat slavery and human trafficking.

The Jesuit human rights lawyer Fr Frank Brennan has been a leading commentator on refugee issues and indigenous land rights. Catholic spokespersons have expressed support for asylum seekers in offshore detention.

Social justice advocacy and theory

In addition to practical charity, the Catholic Church has developed theory on the right ordering of society to ensure justice for the dispossessed. Begun with Leo XIII’s 1891 encyclical Rerum Novarum, the theory is neither socialist nor capitalist, but sees society as a potentially harmonious complex of independent sub-societies like families, businesses, unions and governments, all constrained by requirements of justice.

The 1908 Harvester Judgment of the High Court followed Leo XIII in declaring “reasonable and frugal comfort” the standard for a minimum wage. Archbishop Mannix said “The Catholic Church stands, first of all, for the worker’s right to a living wage,” and spoke on the rights of women and indigenous Australians (texts in ch. 9 of The Real Archbishop Mannix: From the Sources). These ideas were promoted especially by the Campion Society in Melbourne from the mid-1930s; the story is told in Race Mathews’ Of Labour and Liberty: Distributism in Victoria 1891-1966. (review) They appeared from 1940 in the Australian Bishops’ annual Social Justice Statements.

Notre Dame University’s journal Solidarity publishes on Catholic social thought and secular ethics.

(See further in the page on Australian Catholic intellectual life)

Overseas

The Melbourne doctor and nun Mary Glowrey worked in India from 1920 to 1957, treating thousands of poor women patients and training many medical workers.

The Australian Jesuit mission in Hazaribag, north-eastern India, worked among the very poor for several decades from 1951. In Disturbing the Dust, Jesuit missionary Fr Tony Herbert describes his decades of work there with Dalit communities. LaValla School, Phnom Penh, was founded in 1998 for students with physical disabilities. The Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart were very active in health care in Papua New Guinea, as described in J. Lamb, This is mission life: memories of mission: Daughters of Our Lady of the Sacred Heart, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society, 37 (1) (2016), 106-115.

Since 1964, Caritas Australia, the Australian Church’s overseas aid agency, has responded to many disasters and longer-term needs. Its annual Lenten Project Compassion appeal is well-known in churches and schools. Catholic Relief Services helped the new nation of Timor-Leste recover from the devastation of war and occupation. Australians have been prominent in Aid to the Church in Need, the Church’s charity that supports persecuted Christians worldwide.

Sr Irene McCormack was murdered in 1991 by Maoist guerrillas while providing religious and charitable services in a remote region of Peru.