Page Contents

Until the influx of European immigrants from 1947, nearly all Australian Catholics were Irish by birth or heritage. (overview: video lecture)

The Convicts

The convicts who formed the majority of early Catholics were mostly Irish. Some 40,000 Irish were transported. Most were at least nominally Catholic.

Only a few of the First Fleet convicts, such as Hannah Mullins, were Irish. Transportation from Ireland began with the Queen which left Cork in 1791, landing the convicts in Sydney in very poor condition.

Chevalier Robert Sutton de Clonard (b. Wexford, 1751), La Perouse’s second-in-command at Botany Bay in 1788, had served in the French navy at the Chesapeake, an engagement which led to American victory in the War of Independence.

The Men of ’98 and the Castle Hill Rebellion

Some 400 participants and alleged participants in the Irish Rebellions of 1798 and 1803 were transported to Sydney from 1800. Their story is told in Anne-Maree Whitaker’s ‘Swords to ploughshares? The 1798 rebels in New South Wales’, Labour History 75 (1998), 9-21.

Among them were the first priests in Australia, James Harold, James Dixon and Peter O’Neil. Governor King found Fr Dixon cooperative and in 1803 proclaimed toleration for Catholics and allowed Fr Dixon to say mass.

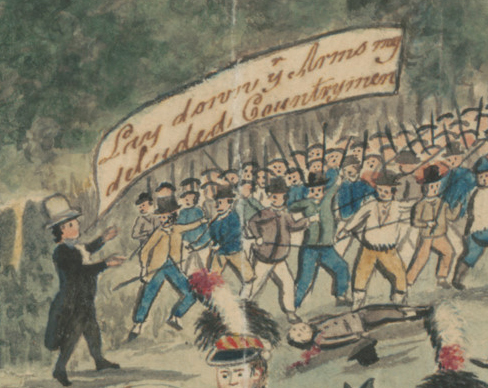

In 1804 Irish convicts at Castle Hill rebelled. Government troops marched quickly to meet them. Fr Dixon and officers remonstrated with the rebels without success, and the rebels were defeated in the “Battle of Vinegar Hill“.

Thereafter the Irish generally chose respectability and assimilation into the increasingly prosperous society of New South Wales. A leader was James Meehan, who did much of the colony’s surveying work in Macquarie’s time and helped many of his countrymen to settle in the Campbelltown area and to the southwest, laying the foundation for Irish chain migration to the Goulburn and Murrumbidgee regions.

During the priestless years of the Macquarie era, Catholic prayer life continued in the Sydney homes of two other “Men of ’98”, William Davis and James Dempsey.

John Plunkett

John Plunkett (b. Co. Roscommon, 1802) was Attorney-General of New South Wales in the 1830s and 40s. He secured the conviction and hanging of the perpetrators of the Myall Creek Massacre and his Church Building Act 1836 gained equal government treatment for Anglicans, Catholics and Presbyterians.

Irish immigration

Many immigrants came from Ireland around the time of the Great Famine of the 1840s and later, including 4000 female famine orphans.

While many settled in the inner cities, some spread in country areas, a few of which became Irish-dominated. Boorowa was described in 1862 as “the headquarters and paradise of the Ryans and might be supposed to be a veritable slice of the County Tipperary.” Val Noone‘s Hidden Ireland in Australia describes the Irish communities of Victoria, some Gaelic-speaking.

Fr McEncroe, the Irish and the Benedictines

Fr Philip Conolly (b. Co. Monaghan, 1786) and Fr John Therry (b. Cork, 1790) arrived in 1820 as the first officially-approved chaplains. But by the 1830s government policy favoured an English-led church and the first two Archbishops of Sydney were English Benedictines.

Tensions arose between English leaders and Irish clergy and people. The story of the leader of the Irish “faction” is told in Edmund Campion’s ‘Archdeacon John McEncroe: An architect of the Australian Church‘, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 39 (2018), 4-12.

The English Benedictine ascendancy ended with the death of Archbishop Vaughan in 1883. His successor, Cardinal Moran, and other Irish bishops, transformed the Australian Church into an Irish-led organisation until 1940.

Irish success in the new land

While political advancement for Catholics in Ireland had made little progress in seven centuries, in the colonies Irishmen soon gained prominent positions. John O’Shanessy (b. Thurles, 1818) became the second premier of Victoria in 1857. Patrick Jennings (b. Newry, 1831) became the first Catholic premier of New South Wales in 1886. Peter Lalor (b. Raheen, Co. Laois, 1827) was the most prominent leader of the Eureka Stockade and later a conservative politician.

Patrick McMahon Glynn (b. Co. Galway, 1855) was one of the “Fathers of Federation” and responsible for including a reference to God in the preamble to the Australian Constitution. Hugh Mahon (b. Co. Offaly, 1857) was the only member ever to be expelled from federal Parliament (for “seditious and disloyal utterances”, 1920)

Ned Kelly

Ned Kelly was born to Irish immigrant parents in 1854. His Jerilderie letter uses Irish grievances to “justify” his killings, calling the police “a parcel of big ugly fat-necked wombat headed big bellied magpie legged narrow hipped splaw-footed sons of Irish Bailiffs or english landlords.” Although no churchgoer, when wounded at the Glenrowan siege he accepted the last rites from Fr Matthew Gibney (b. Co. Cavan, 1835, later Bishop of Perth).

Cardinal Moran and the Irish ascendancy

Patrick Francis Moran, nephew of the leading figure in the Irish “ecclesiastical empire”, Cardinal Cullen, was appointed Archbishop of Sydney in 1884 and named the first cardinal in Australia the next year. Between then and his death in 1911, he ordained nearly 500 priests and officiated at the openings of countless churches and schools. In the 1890s he gave some support to the emerging Labour cause.

He wrote several works on Irish Catholic history and the massive History of the Catholic Church in Australasia (1003 pages). His biography Prince of the Church, by Philip Ayres covers both Irish and Australian periods.

In Moran’s time, large numbers of Irish priests, brothers of the Christian and Patrician orders, and nuns of orders such as the Mercies and Brigidines, arrived to staff the newly expanding parishes, schools and hospitals.

The Irish bishops and religious superiors

The first bishops of Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide, Perth and most non-metropolitan dioceses were Irish, setting the tone for later developments. Around World War I, every archbishop and almost all bishops in Australia were Irish.

The first two Archbishops of Melbourne, James Goold (b. Cork, 1812) and Thomas Carr (b. Co. Galway, 1839) coped successfully with the extraordinary growth of Melbourne and built the massive St Patrick’s Cathedral. Patrick Morgan’s Melbourne Before Mannix portrays the vibrant Irish Catholic community of Carr’s time.

In Sydney the leadership of Moran’s successor, Michael Kelly (b. Waterford, 1850) was generally considered uninspired. His Coadjutor (appointed with right of succession, which did not come to pass) Michael Sheehan had been a leader of the revival of the Gaelic language. His best-selling Apologetics and Catholic Doctrine impressed schoolboys from B.A. Santamaria to Thomas Keneally.

James Duhig (b. Co. Limerick, 1873), Archbishop of Brisbane for 48 years from 1917, favoured cooperation with the established order and was knighted. Unusually for a bishop, he wrote an autobiography.

Many of the first orders of nuns to come to Australia had a background working with the Irish poor. Irish were prominent amongst women religious superiors, such as Sr M. John Baptist de Lacy, founder of St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney, Ursula Frayne, founder of schools in Perth and Melbourne, Mother Xavier Maguire of Geelong, Mother Gonzaga Barry of Ballarat, Mother Vincent Whitty, who established many schools in Queensland, Mother M. Berchmans Daly, founder of St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne, Mother Gertrude Healy, a later hospital adminisrator, and Mary Synan, founder of the Brigidines in Australia.

Male superiors included the Jesuit Fr Joseph Dalton (b. Waterford, 1817), founder of Xavier College and Riverview.

Mannix and the Irish cause

Daniel Mannix (b. Co. Cork, 1864) arrived in Melbourne as coadjutor Archbishop in 1913, after being President of Maynooth Seminary. He was Archbishop from 1917 till his death aged 99 in 1963. By then he was Australia’s best-known churchman and best-known Irishman, principally for his leadership of the anti-conscription campaigns of 1916 and 1917, his involvement with Irish independence, and his patronage of B.A. Santamaria’s “Movement” which precipitated the Labor split of the 1950s.

In 1920 Mannix, by then known for his support of Irish independence, attempted to visit Ireland. The British navy sent a destroyer to arrest him on the high seas and land him in England. “Since the Jutland battle, the British Navy has not scored a success comparable to the capture of the Archbishop of Melbourne,” Mannix said.

The many books on Mannix include Brenda Niall’s award-winning Mannix and J. Franklin, G.O. Nolan and M. Gilchrist’s The Real Archbishop Mannix: From the Sources. (video)

Mannix’s friend, the Irish nationalist priest Fr Hackett, is the subject of Brenda Niall’s The Riddle of Father Hackett.

Rural Catholics: “John O’Brien” and Around the Boree Log

Poor rural Irish Catholic communities created a distinctive culture, celebrated in the poems of “John O’Brien” (Fr Patrick Hartigan, b. Yass, 1878 to Irish parents). Well-known are ‘The Little Irish Mother‘, ‘At Casey’s After Mass‘, and ‘Said Hanrahan‘. A silent film was made in 1925 (Part 1, 41MB) (Courtesy of the National Film and Sound Archive). A first-hand non-fictional account of a similar community is Bernard O’Reilly‘s Cullenbenbong (flimed as Sons of Matthew, 1949)

The story of a small-town Irish Catholic community is told in the centenary history of the Mudgee parish.

Sectarianism and anti-Irish discrimination

Sectarian tensions were heightened in 1868 when a mentally ill Irishman and former seminarian, Henry O’Farrell, shot and wounded the visiting Prince Alfred, and again in World War I because of suspicions of disloyalty by Catholics, especially Mannix.

“No Irish need apply” signs were occasionally found in job ads in the mid-nineteenth century and less overt discrimination occurred up to about 1960. Freemasons, though not explicitly anti-Catholic, favoured one another in employment so de facto disfavoured Catholics. But Orangeism, which is explicitly anti-Catholic, was never strong in Australia. Although Australia had the ethnic composition of Ulster, restraint on both sides avoided the troubles of that region.

Almost none of the Australian squattocracy were of Irish Catholic background. (Rare exceptions were former convicts John Grant in central western NSW and Ned Ryan, “King of Galong Castle.” Patrick Durack (b. Co. Clare, 1834) was a pioneer in western Queensland and the Kimberley, as described in his granddaughter Mary Durack’s Kings in Grass Castles.)

Up to 1960, few Irish names were to be found at the higher levels of banking, insurance, the armed forces, conservative political parties and academia.

Sectarian scandals

In 1900 Cardinal Moran’s right-hand man, Fr Denis O’Haran (b. Enniskillen, 1854), was named as co-respondent in a divorce case. After litigation accompanied by sectarian conflict, a jury found in his favour but doubts remained.

A sectarian cause célèbre began with the flight of Sister Liguori (b. Bridget Partridge, Co. Kildare, 1890) from the Presentation Convent, Wagga, in 1920. She lodged with a Protestant minister and subsequent court cases inflamed sectarian bitterness. The story is told in Maureen McKeown’s The Extraordinary Case of Sister Liguori. (video lecture)

Indigenous Australians

One of the few areas of Catholic endeavour that were not dominated by the Irish was missionary work to aboriginal Australians, which was mostly led by Spanish, German, Italian and French orders.

An exception is the work of the Sisters of St John of God in the Kimberley, recorded in the Heritage Centre Broome. Sister Mary Gertrude (b Co. Clare, 1884) established the Derby Leprosarium. The last Irish nun, Sr Bernadette O’Connor, died in 2007.

Poor communities of mixed Irish-Aboriginal descent (“shamrock aborigines“) were found in some settled rural areas, as described in Warren Mundine’s autobiography.

Eileen O’Connor and the Brown Nurses

Eileen O’Connor, who died aged 28 in 1921 after suffering severe spinal problems almost all her life, is likely the be the first saint from an Irish-Australian background. Her parents were Irish-born. She co-founded Our Lady’s Nurses for the Poor (Brown Nurses) to care for the Sydney sick poor in their own homes. The cause for her canonisation is under way. T.P. Boland’s Eileen O’Connor tells her story, while Jocelyn Hedley’s And Here Begin the Work of Heaven explains her spirituality. Hedley’s Hidden in the Shadow of Love recounts the life of the Nurses after Eileen’s death.

St Patrick’s Day

The great day for the Irish each year has always been St Patrick’s Day (17 March). It has been celebrated enthusiastically, sometimes over-enthusiastically, since at least 1795. Particularly remembered is the 1920 St Patrick’s Day parade in Melbourne, a massive pro-Irish political demonstration led by Archbishop Mannix and 14 (or possibly 20) VC winners on white (or possibly grey) chargers. (video)

Irish organisations

The Hibernian Australasian Catholic Benefit Society provided social security in the era before the welfare state.

Many general-purpose Catholic societies, such as the St Vincent de Paul Society, the Knights of the Southern Cross (founded by Patrick Minahan, b. Killaloe, 1866), the Catholic Federation, the Catholic Club, the Children of Mary and the Genesian Theatre were heavily Irish, while Irish bodies like the Irish National Association and the Gaelic Club were heavily Catholic in membership.

The Australian Labor Party’s Irish heritage

Irish Catholic workers, many in lower-paid jobs, gravitated to the early Labor Party and in some places came to dominate it.

James Scullin, the first Catholic prime minister (1929-32) was the son of Irish Catholic immigrants, as was John Curtin. Joe Lyons and Ben Chifley both had Irish-born mothers and paternal grandparents. Scullin, Lyons and Chifley maintained connections with the Church, Curtin did not. (video of Scullin and Lyons)

The Labor-Catholic nexus was strong in New South Wales, where in the 1950s moderate premiers of Irish-Australian background, James McGirr and J.J. Cahill had close relations with Catholic Church leaders.

J.J. Cahill came from the Marrickville Labor branch. It was said that an old lady arrived late at a branch meeting and accidentally genuflected; when everyone laughed she said “It’s all the same faces.” (source)

In Queensland, the Labor government of T.J. Ryan (1915-19) was followed by long periods of Labor dominance.

In a later generation, Susan Ryan paid tribute to her Irish and Catholic heritage.

Arthur Calwell

Arthur Calwell was the most flamboyantly Irish and Catholic of Australia’s major political figures. During World War I he attracted police suspicion over membership of the Young Ireland Society, and learned Gaelic. As Minister for Immigration in the Chifley government, he instituted a massive immigration program of Eastern Europeans (many Catholic) from 1947 which transformed Australia from “a dull inbred country of predominantly British stock” to its modern multicultural complexion. He was less successful as leader of the federal opposition, 1960-67. He was awarded a papal knighthood.

End of Irish influence

Few priests, religious or other Irish immigrants came to Australia after 1940. The autobiography of Fr Kevin Condon (b. 1932), Here I Am Lord: Memories and Musings of a Wandering Dominican is a rare memoir of an ordinary priest satisfied with his parish work.

Patrick O’Farrell, historian of Irish Australia

Patrick O’Farrell (1933-2013) was the most celebrated historian of both Irish Australia and Catholic Australia. His books include The Catholic Church in Australia: A Short History; Documents in Australian Catholic History 1788-1968; The Catholic Church and Community: an Australian history and The Irish in Australia. A website on his work gives details.

Currently active historians include Jeff Kildea who specialises in Irish and Irish-Australian history and Siobhán McHugh whose radio and oral history work has included the Australian Irish and mixed marriages. Dianne Hall and Elizabeth Malcolm’s A New History of the Irish in Australia (2018) gives a recent overview. (review)

Thomas Keneally, well-known for his historical fiction on Australian, international and Catholic themes, has also written the non-fiction The Great Shame on the Irish famine.

In fiction

Ruth Park’s novels The Harp in the South and Poor Man’s Orange movingly bring to life an inner-city poor Irish Catholic community of the 1940s. Similar rural communities appear in her husband D’Arcy Niland’s novels The Shiralee and Call Me When the Cross Turns Over.

Christopher Koch’s novel Out of Ireland (1999) deals with Irish convict transportation to Van Diemen’s Land.

Colleen McCullough’s popular 1977 novel The Thorn Birds, about the Cleary family on Drogheda station, sold some 33 million copies. The miniseries, filmed in California with a few kangaroos, became the United States’ second highest-rated miniseries of all time.