Page Contents

The Catholic Church in Australia has been characterised by its massive effort in education. The Catholic school system, which in most periods has taught about a fifth of all Australian students, has been conceived as the main cause, under God, of the survival and strength of the Church.

The major Biographical Dictionary of Australian Catholic Educators includes biographies and will include interviews, obituaries and photographs.

A gallery of images of 200 years of Australian Catholic education is available here.

Beginnings

Catholic education began in the penal colony at Parramatta in 1800, with a firebrand teacher, William Maume, exiled because of his leadership role in the 1798 Irish rebellion. In 1802, Fr James Harold, also transported for association with the rebellion, opened an official Catholic school on Norfolk Island. On the mainland, the first ‘Roman Catholic School’, as defined by Governor Philip King, was probably James and John Kenny’s initiative in the Rocks, Sydney in late 1805. An eclectic Farrell Cuffe operated the longest surviving school for Irish children in Sydney town from 1807-1823, before removing to Windsor. Catherine Milling (Fitzpatrick) also established a small Catholic school and choir in Sydney from around 1816.

After the appointment of Fr John Therry as official chaplain, Catholic schools sprang up at Parramatta (1821) and Sydney (1821), but they shared similar characteristics to the pre-1820 schools in terms of colonial funding and governance (rather than church affiliation per se). The Sydney school, established by convicts Andrew Higgins and Robert Muldoon, transited several locations before settling on the St Mary’s Cathedral site, and thus it may be recognised as Australia’s longest surviving Catholic school.

(The above extracted from DJ Gleeson, ‘A revisionist account of early colonial Catholic education’ Australasian Catholic Record 98 (2) 2021)

Catholic schools expanded through the next decades, especially after Governor Bourke’s Church Act of 1836 which gave government funding evenhandedly to the major denominations. Many teachers were laypeople but they were soon joined by members of religious orders, many of them Irish immigrants. (See also the page on Irish Catholic Australians)

The Roman Catholic Orphan School was established at Parramatta in the 1840s. (For more on orphanages see the page on charities.)

Benedictine education

As part of his plans for a Benedictine-inspired church, Archbishop Polding set up Lyndhurst College in Glebe, Sydney, in 1852 as a high-quality, expensive secondary school with a classical curriculum. It closed in 1877.

For the future, the main consequence of Benedictine education was the founding of the Sisters of the Good Samaritan, who began teaching in 1861 and continue to the present.

Withdrawal of state aid

Catholic education faced opposition from those who thought it promoted superstition. The Rev Samuel Marsden about 1807 hoped that Catholicism would soon die out if children were all educated at non-Catholic schools, while Henry Parkes in 1851 called for action against the “grovelling superstition which seeks to fetter and degrade.” In turn Archbishop Vaughan called state schools “seedplots of future immorality, infidelity and lawlessness.”

Each Australian state passed laws to create “free, secular and compulsory” schools and withdrew state aid from church schools – Victoria in 1872, Parkes’ government in New South Wales in 1880, and all states by 1893.

For the next ninety years, the state aid issue was a running sore in Australian politics. Catholics resented that they, a poor community, were forced to pay taxes for state schools they could not in conscience use and to pay again to fund their own schools. Political parties refused to touch the issue for fear of sectarian backlash – even the heavily Catholic Labor Party.

Teaching orders: nuns

Especially in the ninety years without state aid, Catholic infants and primary schools were largely staffed by nuns, as were high schools for girls.

The many books on the history of Australian teaching religious women’s orders include Janice Garaty’s Providence Provides: The Brigidine Sisters in the NSW Province; Margaret Walsh’s The Good Sams; Mary Ryllus Clark’s Loreto in Australia; Marie Crowley’s Women of the Vale: Perthville Josephites 1872-1972; Joan McBride’s When We Are Weak, Then We Are Strong: A History of the Marist Sisters in Australia 1907-1984; Robyn Dunlop’s Planted in Congenial Soil: The Diocesan Sisters of St Joseph, Lochinvar, 1883-1917; Sophie McGrath’s These Women? on the Parramatta Sisters of Mercy; Rosa MacGinley’s Ancient Tradition – New World: Dominican Sisters in Eastern Australia 1867-1958. The overall story is laid out in Rosa MacGinley’s A Dynamic of Hope (its bibliography).

A number of Irish were prominent amongst women religious superiors, such as Ursula Frayne, founder of schools in Perth and Melbourne, Mother Xavier Maguire of Geelong, Mother Gonzaga Barry of Ballarat, Mother Vincent Whitty, who established many schools in Queensland and Mary Synan, founder of the Brigidines in Australia.

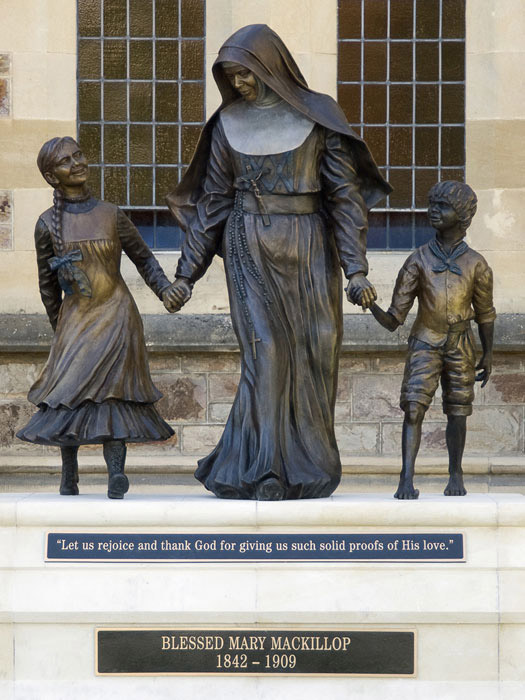

St Mary MacKillop and the Sisters of St Joseph

Mary MacKillop (1842-1909), so far Australia’s only canonised saint, co-founded and was superior of the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart, an order dedicated to the education of the poor. They ran a very extensive network of schools in rural and urban Australian and beyond.

Teaching orders: brothers and priests

The Jesuit fathers, the Christian Brothers, the Marist Brothers, De La Salle Brothers and Patrician Brothers staffed extensive networks of boys’ schools. The Vincentians and Missionaries of the Sacred Heart ran a few schools.

Sport, especially football, was a central part of male education. From 1923, the legendary Brother Henry achieved decades of outstanding football results at St Joseph’s, Hunters Hill. Corporal punishment in the form of “the strap” was a feature of boys’ schools and Catholic schools were slower to ban it than state schools.

Expansion

In the decades before and after 1900, the Catholic school system expanded massively in an effort to make Catholic schooling available for all Catholic children in Australia. Almost every parish had a primary school, usually staffed by nuns. Gradually a network of single-sex Catholic high schools put secondary education within reach of most, while boarding schools were available for remote rural dwellers.

Catholic schools sought to simultaneously match the quality of instruction in, and the exam results of, state schools, while adding religious instruction and creating a complete Catholic culture. The sixpenny “Green Catechism” (1938 edition) was widely used in primary schools to inculcate the basics of faith by rote learning.

Major high schools

The late nineteenth century saw the establishment of a number of large and prestigious boys’ schools which educated many of the leaders of the Australian Church and the wider community: the Jesuits’ Riverview in Sydney and Xavier College in Melbourne, St Joseph’s Hunters Hill, St Joseph’s Gregory Terrace, Rostrevor, and the rural St Stanislaus Bathurst, St Patrick’s Goulburn and St Patrick’s Ballarat. They featured imposing buildings, boarders and football. Major histories of such schools include Greg Dening’s Xavier, Errol Lea-Scarlett’s Riverview and Michael Naughtin’s A Century of Striving: St Joseph’s College, Hunters Hill, 1881-1981.

Girls’ schools followed on a similar plan (of course with different sports), such as Kincoppal-Rose Bay, Loreto Kirribilli and Genazzano Kew.

In 1918 Archbishop Mannix founded St Kevin’s College to provide senior education for inner city Melbourne boys. Early students included B.A. Santamaria, Ted Serong and Damien Parer. (Santamaria’s recollections)

Recollections of Catholic schooldays

The distinctive nature of Catholic education has given rise to a genre of “Catholic childhood” memoirs. Some are grateful for the training in prayer and morality, others angry about guilt and canings.

One of the earliest accounts by a student is Henry Lawson’s brief recollections of Catholic schooling in Mudgee. “John O’Brien’s” poems include a number of vignettes of schooling, such as ‘Tangmalangaloo‘. The 1925 movie of his ‘Around the Boree Log’ contains a reconstruction of a Catholic primary bush school of about the 1870s.

A largely unsympathetic view of brothers’ education in the 1950s is in an excerpt from Ron Blair’s play ‘The Christian Brothers’ (1975). Robert Hughes recollections of Riverview in Things I Didn’t Know (ch. 4) are similar.

A number of former male pupils recall sexual abuse by brothers and priests who taught them. Many such accounts were collected by the Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse; see the page on the abuse crisis.

A convent education was rather a total experience, as recalled by different ex-students in different ways. Germaine Greer’s recollections of Star of the Sea, Gardenvale, Carmen Callil‘s account and Jennifer Dabbs’ novel explain how the combination of tight control with the nuns’ own independence inspired their own feminism. Wanda Skowronska’s Angels, Incense and Revolution: Catholic Schooldays of the 1960s presents a very positive view of an immersive religious education.

The Sixties and the state aid breakthrough

The Goulburn school strike of 1962 showed the Catholic system was at breaking point and public opinion gradually became more favourable. From 1963 the Menzies government gradually introduced federal funding and from the late 1960s very generous public funding supported Catholic schools. (history in Victoria)

During this period the number of religious declined and Catholic schools came to be run by lay staff. Administration became centralised in Catholic Education Offices. Catholic schools still educate about a fifth of Australian students – some 760,000 students in about 1750 schools.

Some conservative Catholics felt that the systemic Catholic schools were insufficiently Catholic and set up a few more traditionalist alternatives, such as the Pared schools in Sydney and Melbourne.

Religious instruction in state schools

The Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, begun by Cardinal Gilroy in 1957, provides religious instruction to Catholic students in state schools across Australia, using mostly lay volunteers. (history in NSW)

Adult education

The Thomist philosopher Austin Woodbury founded the Aquinas Academy in Sydney in 1945 to teach philosophy to the laity. It was well-attended for thirty years. (Woodbury’s lectures) The Academy later taught spirituality and psychology. (Its history)

Since the Second Vatican Council many more lay people have undertaken higher religious education. The Broken Bay Institute specialises in theology and canon law.

Seminary education

Polding established St Mary’s Seminary in 1838.

(Star Photo; State Library of New South Wales)

Around 1900 the firm of Sheerin and Hennessy designed the spectacular St Patrick’s Seminary, Manly. It trained generations of priests for many Australian dioceses until its relocation in 1995. A history is Kevin Walsh’s Yesterday’s Seminary, while Chris Geraghty’s The Priest Factory gives a highly-coloured picture of life in the seminary around 1960.

From 1909 to 1977, the remote Springwood Seminary handled the first three years of seminarians’ training. Memoirs include the partly hostile Cassocks in the Wilderness by Chris Geraghty, Trapped in a Closed World by Kevin Peoples, with a more positive view in Victor Michniewicz’s St Columba’s Springwood.

In 1923, Archbishop Mannix opened Corpus Christi Seminary, Werribee. It expanded to Glen Waverley in 1960, but both were merged into the Clayton campus in 1973. Paul Casey’s Where Did All the Young Men Go? contains many recollections of the 1960s.

Following some doubts about the orthodoxy of some seminary training, Vianney College was opened in Wagga Wagga by Bishop Brennan in 1992.

Each major order of priests had its own seminary, such as the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart at Douglas Park, the Jesuits at Sevenhill, Watsonia and Pymble, and the Redemptorists at Galong. The training of nuns tended to be less centralised.

Memoirs of training in religious orders include John Redrup’s Banished Camelots (on the Marist Brothers’ juniorate at Mittagong), Gerard Windsor’s Heaven Where the Bachelors Sit, and Cecilia Inglis’s Cecilia. A juniorate is the setting of Fred Schepisi’s 1976 movie, The Devil’s Playground. (trailer)

University colleges

Catholic residential colleges at secular universities were founded with the hope that they would contribute to intellectual life but that has rarely occurred. St John’s College was founded at Sydney University in 1858, contrary to general Church policy against involvment with secular universities. The history of Newman College, founded at Melbourne University by Mannix, is described in Niall, Dunin and O’Neill’s Newman College: A History 1918-2018. (JACHS review)

Later colleges are St Mary’s at Melbourne, Sancta Sophia at Sydney U, John XXIII at ANU, Mannix at Monash, St Leo’s at the University of Queensland (history), Aquinas at Adelaide, Warrane at UNSW, St Thomas More at UWA, St Albert’s at UNE, Saints at JCU, and John Fisher at UTas.

Catholic universities

Considerable efforts were made to found a Catholic university in Sydney around 1950 but were unsuccessful.

The Australian Catholic University was founded in 1991 by amalgamating four teachers’ colleges. It has since expanded to a complete university. The story is told in John Hirst’s Australia’s Catholic University: The first twenty-five years. (review) ACU contains the P.M. Glynn Institute for religion and public policy and the Golding Centre for Women’s History, Theology and Spirituality.

The University of Notre Dame Australia was established in Fremantle in 1989 and expanded to campuses in Sydney and Broome. Its degrees include a core curriculum of philosophy, ethics and theology. Research strengths include medicine and ethics and society.

Besides seminaries, many centres and institutes have provided higher tertiary education. Some have become members of the University of Divinity in Melbourne and the Sydney College of Divinity. The Melbourne John Paul II Institute for Marriage and Family offered postgraduate degrees in such areas as bioethics and pastoral care from 2001 to 2018. The Catholic Institute of Sydney researches and teaches on theology, philosophy, and the humanities.

Campion College opened in western Sydney in 2006 as Australia’s first liberal arts college. It offers an integrated introduction to the ideas of Western civilisation with a focus on traditional Catholic thought.

A smaller venture in a rural setting is the Augustine Academy.