Page Contents

Early years

The convicts who formed the majority of early Catholics were mostly men, but women soon came to form a large part of Australian Catholics. The Census of 1828 showed 6135 male and 2091 female Catholics.

The reverse was true in later times and recently a considerable majority of active Catholics are women.

In 1818, with no priests in the colony, Catherine Fitzpatrick trained a choir that would later become the nucleus of St Mary’s Cathedral choir.

Sisters of Charity and Good Samaritans

Five Sisters of Charity arrived in Sydney from Ireland in 1838 to work with convicts and the sick poor. Relations with Archbishop Polding were not always harmonious, as recounted in Moira O’Sullivan’s A Cause of Trouble? Irish Nuns and English Clerics. (JACHS review) They founded St Vincent’s Hospital, still one of the leading hospitals in Australia. Their later history is detailed in Danielle Achikian’s Ministry of Love.

In 1857 the Sisters of Charity oversaw the foundation of the first Australian women’s religious order, the Sisters of the Good Samaritan.

Since that time the educational, nursing and charitable work of the Church has been very heavily dependent on women, both religious and lay.

Religious women greatly outnumbered priests and brothers, and so took on the majority of tasks, especially in teaching and nursing. Rosa MacGinley’s A Dynamic of Hope: Institutes of Women Religious in Australia (2002) surveys the work of religious orders (its bibliography). Anne O’Brien’s God’s Willing Workers: Women and Religion in Australia (2005) surveys the wide range of work done by both Catholic and Protestant religious women.

Caroline Chisholm

Catholic laywoman Caroline Chisholm responded to the plight of young immigrant women in 1840s Sydney. Her employment agency found safe jobs for many in city and rural areas and her immigration scheme brought many more. The most recent of several books on her and her work is Sarah Goldman’s Caroline Chisholm (JACHS review) (source materials)

Nuns’ charities

In the nineteenth century, nuns originally aimed at charity more than educational work, and in the absence of a welfare state, their role was central. By 1900 in NSW, “Sisterhoods operated: five hospitals, including a women’s psychiatric hospital and a hospice; seven orphanages; a foundling hospital; a residential school for deaf children; three industrial schools; a servants’ home and training school; two refuges for former prostitutes; a home for the aged poor and a women’s night refuge. The Sisters also undertook non-institutionally based work with immigrant servant girls; the sick poor in their homes; patients in Sydney Hospital; prisoners in Darlinghurst Gaol; the inmates of government aged asylums and girls in the Government Reformatory and Industrial School.” (Lesley Hughes, ‘Catholic Sisters and Australian Social Welfare History,’ ACR 87 (2010))

Education by nuns

Especially in the ninety years after the withdrawal of state aid for church schools around 1880, Catholic infants and primary schools were largely staffed by nuns, as were high schools for girls.

The many books on the history of Australian teaching religious women’s orders include Janice Garaty’s Providence Provides: The Brigidine Sisters in the NSW Province; Mary Ryllis Clark’s Loreto in Australia; Marie Crowley’s Women of the Vale: Perthville Josephites 1872-1972; Joan McBride’s When We Are Weak, Then We Are Strong: A History of the Marist Sisters in Australia 1907-1984; Robyn Dunlop’s Planted in Congenial Soil: The Diocesan Sisters of St Joseph, Lochinvar, 1883-1917; Sophie McGrath’s These Women?; Rosa MacGinley’s Ancient Tradition – New World: Dominican Sisters in Eastern Australia 1867-1958.

A number of Irish were prominent amongst women religious superiors, such as Ursula Frayne, founder of schools in Perth and Melbourne, Mother Xavier Maguire of Geelong, Mother Gonzaga Barry of Ballarat, Mother Vincent Whitty, who established many schools in Queensland and Mary Synan, founder of the Brigidines in Australia.

The trials of surviving and then leaving a religious life are described in Cecilia Inglis’s readable memoir, Cecilia: An Ex-Nun’s Extraordinary Journey.

A convent education was rather a total experience, as recalled by different ex-students in different ways. Examples are Germaine Greer’s recollections of Star of the Sea, Gardenvale and Wanda Skowronska’s Angels, Incense and Revolution: Catholic Schooldays of the 1960s.

St Mary MacKillop

Mary MacKillop (1842-1909), so far Australia’s only canonised saint, co-founded and was superior of the Sisters of St Joseph of the Sacred Heart, an order dedicated to the education of the poor.

She was excommunicated for “insubordination” in 1871 but the decision was reversed the next year. In 1873-5 she visited Rome and gained qualified approval for the order’s rule of life.

She was canonised in 2010. A museum is located next to her tomb in North Sydney, and another at Penola, SA, where she set up her first school.

Hospitals

Nuns provided the leadership and nursing staff of a number of prominent Catholic hospitals. Irish were prominent amongst women religious superiors, such as Sr M. John Baptist de Lacy, founder of St Vincent’s Hospital, Sydney, Mother M. Berchmans Daly, founder of St Vincent’s Hospital, Melbourne and Mother Gertrude Healy, a later hospital adminisrator. Sr Bernice Elphick, Mother Rectress of St Vincent’s, Sydney, from 1963, was legendary both as an adminstrator and as a fundraiser, especially from the hospital’s heart patient Kerry Packer.

Gertrude Abbott‘s informal religious community of women ran St Margaret’s maternity hospital in inner Sydney from 1894, initially for unmarried pregnant women. St Joseph’s Foundling Hospital began in Melbourne in 1901 for the same purpose, to take in “erring but often innocent young women” and look after them and their babies.

Lay Catholic women

Every Australian Catholic had a mother, the great majority of them crucial in developing their children’s faith. Their role is celebrated in “John O’Brien”‘s poem ‘The Little Irish Mother‘. His poem ‘The Trimmin’s on the Rosary‘ recalls women’s direction of spirituality in the home.

Many women energetically organised charity work, visitation of the sick, fetes, tuckshops, fundraising and social events. The work of decorating altars with flowers and cleaning churches was almost all done by women. Some organised work on a larger scale, such as hospital charity leader Mary Barlow and Lena Santospirito who was very active in welfare work for the Italian community in Melbourne in the 1940s and 1950s.

Priests’, brothers’ and seminarians’ work was made possible by the hard work of generations of housekeepers. The few now remembered include the Virgona sisters, for many years housekeepers to Archbishop Mannix at Raheen. “John O’Brien”‘s poem ‘Josephine‘ pays tribute to presbytery housekeepers.

Enclosed orders

French Carmelites arrived in Australia in 1885 and settled in Dulwich Hill, Sydney. Other Carmels have been founded.

Benedictine nuns arrived in Sydney from England in 1849 and for many years their community lived at Subiaco, Rydalmere. Since 1988 they have been established at Jamberoo in the Southern Highlands of NSW. The 2007 ABC TV series The Abbey followed young women trying out the life at Jamberoo.

Indigenous Australians

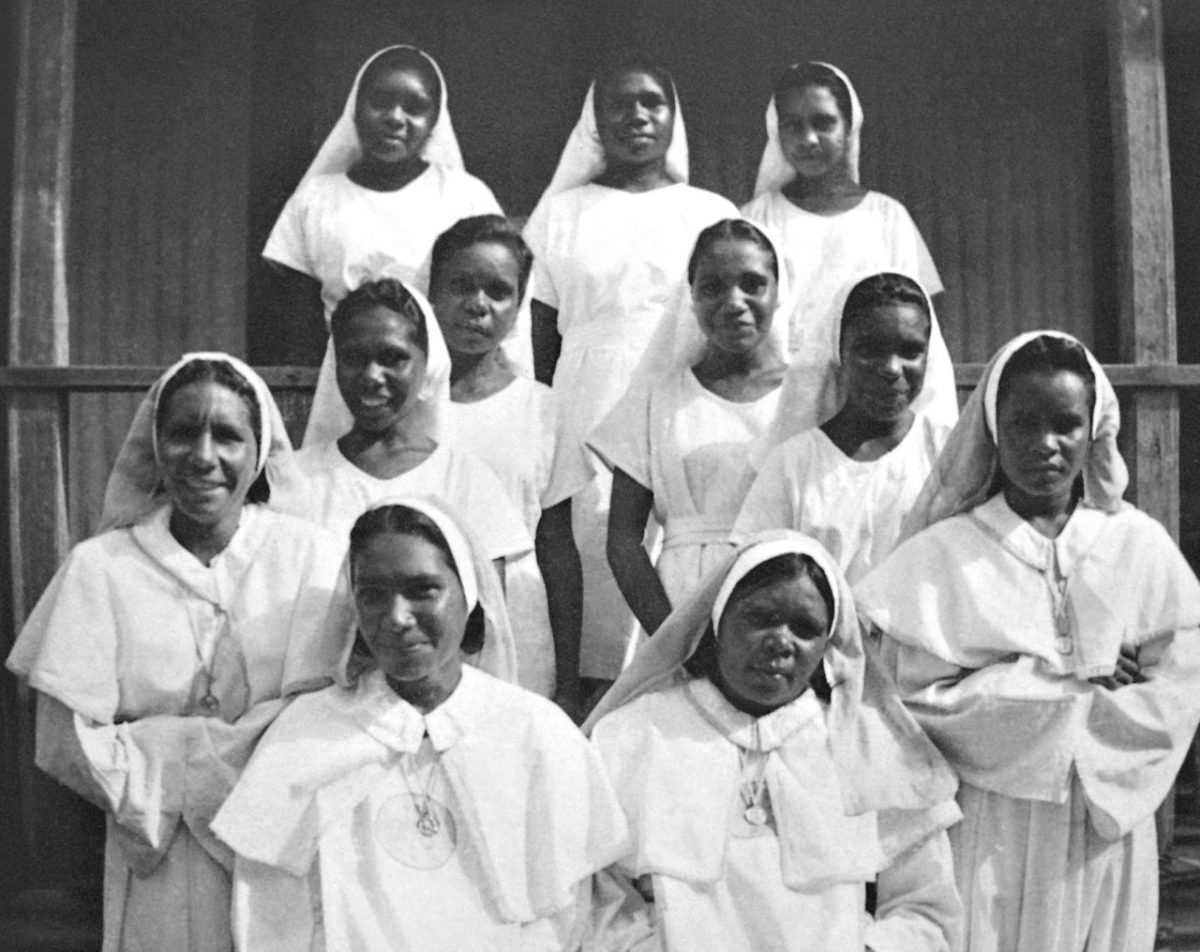

Christine Choo’s book Mission Girls tells the story of aboriginal women on Catholic missions in the Kimberley. An aboriginal order of nuns that existed for a short time is described in her article Daughters of Our Lady, Queen of the Apostles—the first and only order of Aboriginal sisters in Australia, 1938-1951, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 40 (2019), 103-130.

The story of the Sisters of St John of God in the Kimberley is recorded in the Heritage Centre Broome. Their nursing work with indigenous patients in the Derby Leprosarium (led by Mother Mary Gertrude) is recounted in Charmaine Robson’s thesis,

Care and control: the Catholic religious and Australia’s twentieth-century ‘indigenous’ leprosaria 1937-1986. An Australian order, the Sisters of Our Lady Help of Christians, worked in leprosariums and later in domestic work in seminaries.

Notable aboriginal Catholic women include the New Norcia telegraphist Mary Ellen Cuper; Martina, the first of Francis Xavier Gsell’s “150 wives” who fled arranged marriages; and Marjorie Liddy, whose bird image was used on the vestments at World Youth Day 2008.

Mum Shirl‘s work for NSW prisoners and Redfern residents in the 1960s to 1990s is legendary.

Eileen O’Connor and the Brown Nurses

Eileen O’Connor, who died aged 28 in 1921 after suffering severe spinal problems almost all her life, co-founded Our Lady’s Nurses for the Poor (Brown Nurses) to care for the Sydney sick poor in their own homes. The cause for her canonisation is under way. T.P. Boland’s Eileen O’Connor and John Hosie’s Eileen tell her story, while Jocelyn Hedley’s And Here Begin the Work of Heaven explains her spirituality. Hedley’s Hidden in the Shadow of Love recounts the life of the Nurses after Eileen’s death.

Sister Liguori

A sectarian cause célèbre began with the flight of Sister Liguori from the Presentation Convent, Wagga, in 1920. She lodged with a Protestant minister and subsequent court cases inflamed sectarian bitterness. The story is told in Jeff Kildea’s Sister Liguori: The Nun Who Divided a Nation. (video lecture)

Orphanages and Magdalen laundries

In earlier times, large numbers of parentless and homeless children and teenagers were cared for in underfunded institutions, many run by nuns, such as the Roman Catholic Orphan School, Parramatta (1841-1866). Conditions varied and many former residents have negative memories, as described in James Franklin, Convent slave laundries? Magdalen asylums in Australia, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 34 (2013), 70-90.

Catholic women’s organisations

The Catholic Women’s Social Guild was established in Victoria in 1916 and established a home for poor parents in delicate health. The Catholic Women’s Association of NSW, headed by Mary Barlow, was very active in hospital charity work. Those organisations later amalgamated to form the Catholic Women’s League Australia.

In the early twentieth century, large numbers of girls in parishes joined the Children of Mary sodality (photo).

The Catholic women’s movement The Grail was founded from The Netherlands in 1936 and has undertaken many projects. Its history is described in Alison Healey’s ‘The grail – 75 years in Australia: An international women’s movement and the Australian church‘, Journal of the Australian Catholic Historical Society 31/2 (2011), 27-38.

Enid Lyons

Enid converted to Catholicism when she married Joe Lyons at the age of 17. They had twelve children. When he died in office as prime minister in 1939 she at first withdrew from public life but in 1943 became the first woman to be elected to the House of Representatives. (audio of maiden speech) In the early 1950s she was the first woman in federal Cabinet. Her account of her time in Parliament was titled Among the Carrion Crows. Her story is told in Anne Henderson’s Enid Lyons: Leading Lady to a Nation. (video) (interviewed on her life)

Dorothy Tangney was elected the first woman Senator in 1943.

Many other firsts for women were achieved by Dame Roma Mitchell – the first woman judge, QC, university chancellor and state governor.

Australians overseas: Mary Glowrey, Rosemary Goldie and Irene McCormack

Melbourne doctor Mary Glowrey, believed to be the first Catholic religious sister to work as a doctor, practised for 37 years from 1920 in India, treating mostly poor women.

Many women nuns worked as teachers and nurses in Papua New Guinea and the Pacific Islands. (Interview of Sr Berenice Twohill on living through the Japanese occupation of Rabaul)

The theologian Rosemary Goldie was Undersecretary of the Pontifical Council for the Laity from 1967 to 1976, as described in her autobiography, From a Roman Window.

Sr Irene McCormack, a missionary to Peru, was executed by Maoist guerrillas in 1991.

Intellectual life

Sr Veronica Brady, an expert on Patrick White and Judith Wright, was a supporter of women’s ordination.

The first female premier of New South Wales, Kristina Keneally, holds a masters degree in feminist theology.

In recent years, many women, Catholic and Protestant, have become well-known in theology.

More recent Catholic intellectual leaders include theologian Tracey Rowland, ethicist Bernadette Tobin and linguist Anna Wierzbicka.

Geraldine Doogue‘s distinguished journalism career with the ABC included almost twenty years as host of religion program Compass.

ACU’s Golding Centre for Women’s History, Theology and Spirituality coordinates work on Catholic women’s studies. (background)

Sexual abuse crisis

A smaller proportion (about 20%) of victims and a tiny proportion of perpetrators of sexual abuse in Catholic institutions were female.

Chrissie Foster’s Hell on the Way to Heaven recounts the tragedy of her two daughters whose lives were destroyed by a pedophile priest.

The Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse conducted a case study into the Mercy Sisters’ St Joseph’s Orphanage, Neerkol, Rockhampton, and found the nuns had acted cruelly and facilitated sexual abuse by priests.

In 1982 Mercy Sisters Kathleen McGrath and Patricia Vagg of Mortlake Vic reported their parish priest, Gerald Ridsdale, to Bishop Mulkearns for sexual abuse. Ridsdale was moved to another parish and the nuns ordered to keep quiet.

In fiction

Ruth Park’s novels The Harp in the South and Poor Man’s Orange movingly bring to life an inner-city poor Irish Catholic community of the 1940s.

The popular 1991 TV series Brides of Christ portrayed the tensions in religious orders in the 1960s in a soap opera style … video clip